Here we Joh again! Carmody promotion a throwback to Terry Lewis

There he is again! The ghost of former Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen haunts Queensland politics (Image via zgeek.com)

The controversial promotion of Tim Carmody be Queensland’s chief justice is a throwback to the days of Joh, writes Steve Bishop, who wonders how long he can possibly last.

THE INSERTION OF JUNIOR JUDGE Tim Carmody

as Queensland’s chief justice is probably the most outrageous and

cynical disregard for proper process in the State’s policing and justice

systems since Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen promoted inspector Terence Lewis to Assistant Commissioner in 1976.

There is no suggestion that Judge Carmody is in any way corrupt, as Terry Lewis was when personally selected by Bjelke-Petersen.

But what is identical is the way in which a Liberal-National Party Queensland government has promoted a person whom it believes is supportive of the party’s policies. And does so in flagrant disregard for past practice, best practice and independent advice.

The LNP’s regard for Judge Carmody probably goes back to 1996, when the Liberal-National Coalition Government appointed the Connolly-Ryan Commission of Inquiry, in what was widely seen as an attempt to undermine the Criminal Justice Commission, the Fitzgerald Inquiry’s legacy to fighting organised crime and corruption.

The National Party has never forgiven the Fitzgerald Inquiry into corruption, which resulted in voters ending its 32-year reign in government and four of its ministers being gaoled.

Tony Fitzgerald put it like this:

'The Connolly-Ryan inquiry was…set up to discredit the reforms

which had been introduced on my recommendation so that they could be

dismantled with minimum community disquiet, but that exercise failed

when the Supreme Court stopped the farce because of Connolly's manifest

bias.'

For these reasons, it might have been wise for the Newman Government to omit all references to the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry

But when current LNP Attorney-General Jarrod Bleijie gave Tim Carmody

his first major leg-up, promoting him to the District Court bench and

to chief magistrate nine months ago, Mr Bleijie’s speech

nominated only two highlights of Mr Carmody’s time at the Bar — one of

them was being counsel assisting at the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry.

The chair of the Criminal Justice Commission at the time of the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry, Frank Clair, provided an official report (September 1997) on the effect of the inquiry on the CJC.

He wrote:

'Lengthy responses had to be prepared by CJC officers to meet

assertions, often ill-informed, foreshadowed by counsel assisting in

reports on past investigations as submissions which were to be placed

before the Inquiry.'

Mr Clair criticised

'... the sometimes aggressive and unnecessarily adversarial

approach taken by those associated with the (Connolly-Ryan) Inquiry.'

And he said the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry had

'... significantly hampered the performance of the normal functions of most of the divisions of the CJC.'

It was estimated by the Opposition that the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry wasted between $11 and $14 million of taxpayers’ money in addition to distracting the CJC from its crime and corruption fighting role.

After the Connolly-Ryan Commission had been shut down

because of its bias, the Liberal-National Coalition Government created a

Crime Commission in competition with the Criminal Justice Commission

and, in one of its last major appointments, appointed Mr Carmody as its commissioner.

The elevation of Mr Carmody in 2013 to chief magistrate was the first

of Attorney-General Bleijie’s judicial recommendations after taking

office. He would have taken advice from his director-general, John Sosso.

Mr Sosso was National Party Premier Rob Borbidge’s deputy director-general in 1996 when the Connolly-Ryan Inquiry was instituted.

As mentioned by Tony Fitzgerald QC, whose inquiry exposed the corruption of Police Commissioner Terry Lewis and the Bjelke-Petersen Government, Mr Sosso was influential in the Bjelke-Petersen government:

'When the Inquiry was established in 1987, the National Party

Attorney-General was advised and influenced by a small ambitious group

of Justice Department bureaucrats. The Attorney-General appointed one,

John Sosso, as Secretary to the Inquiry. Sosso didn't last long in that

role but returned to the Justice Department which, as the Inquiry's

report notes, did little willingly to assist the Inquiry.'

Junior inspector Terry Lewis was elevated over more than 100 more senior officers by the National Party Government in 1976 (Fitzgerald Report, p44) to become assistant commissioner.

The decision caused an outrage and led to the resignation of honest commissioner Ray Whitrod, closely followed by the promotion of Lewis to commissioner.

Chief Magistrate Carmody has been elevated over the bewigged heads of

22 Supreme Court judges and more than 30 District Court judges. The

most senior of the Supreme Court judges – and the person who would

almost certainly have become chief justice under another government – is

Margaret McMurdo.

Selection in this way, as practised in every Australian state, means

that the government of the day is very properly stopped from

politicising the position by appointing a lackey. It is inconceivable

that the Government gave proper consideration of the merits and

experience of all 22 Supreme Court judges and found them all wanting.

So it is plain that, like the appointment of Terry Lewis back in

1976, the Newman Government plumbed the depths of promotable

possibilities and came up with a junior judge who, it had reason to

believe, will be sympathetic to its policies.

Before Chief Magistrate Carmody’s appointment former Solicitor-General Walter Sofronoff QC wrote:

'Judge Carmody should himself quell this present

unfortunate and unhealthy speculation about him by stating forthrightly

that he would not accept an appointment to the office of Chief Justice

if it were offered to him.'

Award-winning journalist (and regular IA contibutor) Evan Whitton

has pointed out that there is more than one precedent for judges to

refuse the appointment of chief justice if they feel that proper process

has not been followed by the government.

Judge Ted Douglas

had fallen foul of a Queensland Labor Government and, in 1956, was

passed over when he was expected to be appointed chief justice. Instead,

the government offered the post to Justice Roslyn Philp. Philp did the honourable thing and declined.

However, Chief Magistrate Carmody, despite the risk of his

appointment causing dissent and a rift among judges and barristers,

accepted.

The dissent and rift are spectacular and unprecedented.

Tony Fitzgerald QC said:

"People whose ambition exceeds their ability aren’t all that

unusual. However, it's deeply troubling that the megalomaniacs currently

holding power in Queensland are prepared to damage even fundamental

institutions like the Supreme Court and cast doubt on fundamental

principles like the independence of the judiciary."

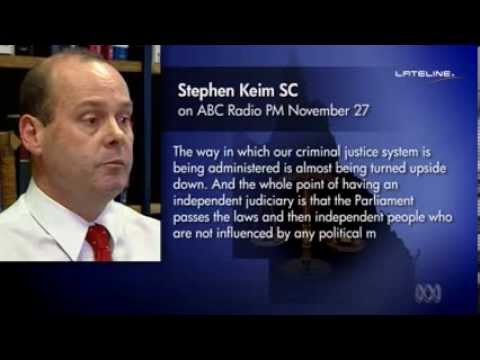

Former Supreme Court judge George Fryberg told the ABC:

“For the chief justice, you need qualities like a very

powerful intellectual ability. Tim's quite bright, but I don't think

he's in the league that is required for chief justice."

Another former Supreme Court judge, Richard Chesterman QC, told the Courier-Mail:

“A judicial officer whose meteoric rise has been associated with

public support for a government cannot command the confidence and

respect a chief justice must have.”

After the appointment, Mr Sofronoff told the ABC:

“Judge Carmody is somebody who has by his own actions identified

himself too closely with the Government. Judge Carmody is a person who

has none of the necessary qualities of a chief justice of a supreme

court of a state of Australia… He shouldn't be Chief Justice. He should

do the gracious thing and realise that all of this has been a horrible

mistake and say that he wouldn't accept the appointment.”

Bar President Peter Davis QC resigned from his position saying he had no faith in the selection process.

He continued:

"The Government has said that they consulted widely on the

appointment. My sense though is that there was little, if any, support

for the appointment within the legal profession and little, or none,

within the ranks of sitting Supreme Court judges. Senior figures warned

against the appointment and some have spoken out against it since its

announcement."

This latest example of the Newman Government’s disregard for the

separation of powers, proper process, transparency and the voting public

comes only a month after it passed legislation scrapping

the public’s independent watchdog, the Crime and Misconduct Commission,

and replacing it with a lapdog Corruption Commission to be controlled

by a government-appointed chair.

The question now is: how much more pressure will be brought to bear

on this appointment and how long will Judge Carmody feel able to reside

in a house where he is not wanted?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

No comments:

Post a Comment